The woman and her legend

History Matters

by Cheryl Lassiter

Hampton Union, October 27, 2015

[The following article is courtesy of the Hampton Union and Seacoast Online.]

It’s my guess that most people in town would not be surprised to learn that the most frequently asked questions by visitors to the Tuck Museum, especially around this ghostly time of year, are those about Goody Cole, the Witch of Hampton.

For the benefit of those who might never have heard of Hampton’s most famous citizen: Goody Cole, whose given name was Unise (alternately, Eunice), was a seventeenth-century miscreant whose hateful presence disturbed the town’s peace, leaving the magistrates no other choice but to physically punish her, and when that didn’t produce the desired good behavior, to charge her with witchcraft.

Unise Cole has been portrayed as a foul-tempered misanthrope imbued with magical powers. In modern times she has been variously feared and pitied, and has achieved minor cult status as a witch and renowned victim of a cruel belief system. The truth is, the facts of Goody Cole’s existence present themselves like the prison she was so often in: dark, windowless, and having a heavily barred door to further inquiry. It is impossible to know who she really was and what her desires and demons might have been. But we can try.

From England to America

In 1635, a maid named Eunice Giles married a sawyer named William Coules at the medieval Anglican church of St. Dunstan’s in the parish of Stepney, Middlesex, England, just outside of the walled city of London, adjacent to the East India Company’s sprawling shipyard in Blackwall. I believe this was the Unise and William Cole who arrived in New England during the summer or fall of 1636. They lived at Mount Wollaston, south of Boston, until late 1637- early 1638, when they were among the first settlers of Exeter, New Hampshire. In 1640 the town of Hampton granted land to William, but he continued to appear in the Exeter records until about 1644, in which year it is supposed he and Unise moved to Hampton. Once here, Unise’s legal troubles began almost immediately. Long before her first trial for witchcraft, she was fined, set in stocks, “admonished,” and even whipped for various infractions of the law, much of it related to bad relations with her neighbors. Neither the civil authorities nor her husband, who once joined her in railing against a perceived injustice, could subdue her for long.

During the quarter century from her first witchcraft trial in 1656 until her death in 1680, Unise spent more than half the time in prison. In all, she was whipped at least two, perhaps three, times, was hauled before the court on at least eight occasions, fined twice, admonished once, twice put under a bond, set in the stocks, searched for witch-marks, watched for diabolical imps, and, near the end of her life, was locked in leg irons and imprisoned one final time.

First trial for witchcraft

Twenty-six witnesses testified at her first trial for witchcraft, held in Boston. The main evidence brought against her was the witch-marks discovered on her body at her first whipping. The reason for the whipping seems to have been related to her involvement in the death of a (possibly deformed) child. Witnesses also implicated her in the death of a bedridden man, said she had killed their cattle through demonic agency, and that she had had an uncanny knowledge of a private conversation.

Convicted on a lesser charge, Unise was kept in the Boston prison until early 1660. When she returned home she was immediately back in trouble. For calling her neighbors despicable names, she was again whipped and sent back to prison.

When William died in 1662 Unise petitioned the court for release, which was granted. Unable to abide by the terms of the release, she was sent back to prison for a third time—coincidentally on the morning after she had been observed discoursing in her house with the Devil himself.

Her house and land were taken from her and she became a ward of the town, which paid a yearly charge to keep her incarcerated. Eight years later, over 70 years old and homeless, she was freed from prison. When she returned to Hampton the town put her in a cottage near the meeting house and grudgingly provided her with food and wood.

Second trial for witchcraft

The trouble again started up, with a whining pup in the meeting house, threats made to the night’s watchmen, and the enticing of a nine-year-old girl. The last offense was deemed witchcraft and in 1673 Unise was again put on trial in Boston. The prosecutors, John Sanborn and/or Nathaniel Weare, threw the kitchen sink of testimony at her, even bringing in decades-old evidence to wring out a conviction. Yet, after all their hard work, the jury stubbornly refused to find her legally guilty. Unise again returned to Hampton. Nothing more was heard of her by way of the court until 1680 when she was again accused of being a witch, for which she was locked in leg irons and held in the local prison. One month later she died, and a legend was born.

Early legends

By the nineteenth century, tales of old Goodwife Unise Cole were circulating in written form thanks to the pens of local historians like Edmund Willoughby Toppan (1808-1845) and Joseph Dow (1807-1889), and the poems of John Greenleaf Whittier (1807-1892) of Amesbury, Massachusetts.

Toppan was the first person, as far as is known, to set down the Cole lore as it existed in his time. He looked with a bemused eye upon claims of Unise’s “alliance with the Devil,” observing that despite her reputation as a fearsome witch, the “young people of that day” delighted in antagonizing her with tricks. Concerning her death, Toppan wrote that after a few days of not seeing her out and about, the townspeople “plucked up courage enough to break into the house” and found her dead. They buried her and drove a stake into the grave, with a horseshoe attached, “to prevent her from ever coming up again.” When Toppan was a student at Hampton Academy, a “little mound of earth was pointed out [to him] as the veritable grave of the once powerful Eunice Cole.”

Whittier also took an interest in the lore. Much of today’s popular perception of her can be traced back to the scratchings of his imaginative quill. The 1864 ballad “Wreck of Rivermouth” recast a real-life 1657 shipwreck near the mouth of the Hampton River into a doomed fishing excursion to the Isles of Shoals. The poet places “the mad old witch-wife” in a riverside shack, where she is able to curse her antagonists as they sail merrily by. When a young lady onboard makes fun of the “bent and blear-eyed poor old soul” sitting at her door a-spinning, Unise conjures up a storm to teach her a lesson. Whittier must have felt a pang of guilt for abusing her memory in this way; at the end of the tale he gives her a heart: as she sees the sinking ship, a tear stains her cheek and she is utterly shaken that her “words were true.”

Joseph Dow, who wrote the History of Hampton, just stuck to the facts.

The Goody Cole Society

The Great Depression with its Dust Bowl, dispossessed farmers, and homeless vagabonds had sparked America’s social imagination and fired enormous interest in the lives and sufferings of ordinary people. It was during this time that Unise Cole’s life story became an object lesson in injustice, and her reputation as a witch rocketed to celebrity status. She was Hampton’s most well-known citizen, with a story ripe for exploitation.

In 1937 the Goody Cole Society was formed to “restore” Unise Cole to the “citizenship” of which she had been deprived by many years of imprisonment, and at the town meeting in 1938 residents voted to give back her “rightful place as a citizen of the town of Hampton.” Two weeks later she and her latter-day champions starred in a nationally broadcast radio program to dramatize the event.

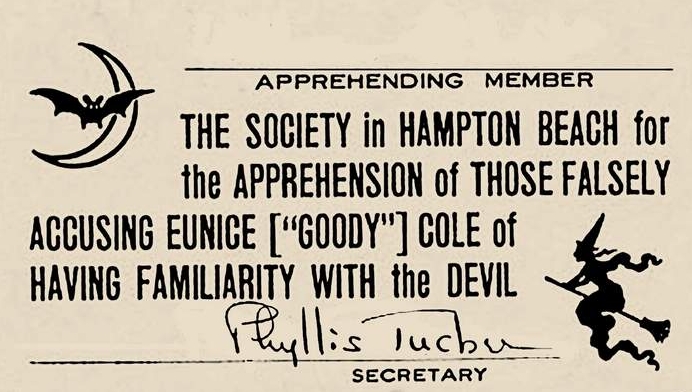

The Goody Cole Society Membership card (Hampton Historical Society)

As the star of the town’s 300th birthday, held in August 1938, her imagined likeness was emblazoned on pamphlets, plaques, street signs, commemorative coins, and an air mail cachet; there was a Goody Cole doll and a Witch of Hampton booklet. Goody Cole scenes appeared in the town’s historical pageant. An entire day was devoted to her memory, with a special ceremony, attended by local and state dignitaries and a national celebrity, to restore her rights as a citizen of Hampton.

Later legends

In 1937, Haverhill, Massachusetts newspaperman William D. Cram invented the enduring story of Goody Cole’s magic well, placing it alongside her riverside shack at The Willows on Sargent’s Island. Then in the early 1960s, just in time for another town anniversary, came a spate of sightings of the ghost of Goody Cole (as well as the installation at the local museum of a large lump of granite in her honor).

A well-treated witch?

Since those earlier times, the town’s demeanor has taken a more sophisticated turn: the two most recent town anniversaries were devoid of any new Cole lore. But she is far from forgotten—a musical album about her legend has been produced, information about her life is one of the top visitor requests at the Tuck Museum, and the Witch of Hampton remains as well-known to the town’s children as the local candy store. Remembrances of her have become, in their own way, part of the lore. It begs the question—has any other “witch” in history been treated so well post mortem as our own Goodwife Unise Cole?

History Matters is a monthly column devoted to the history of Hampton and Hampton Beach. Cheryl Lassiter is the author of “The Mark of Goody Cole: a tragic and true tale of witchcraft persecution from the history of early America” (2014). Her website is www.lassitergang.com.